Images of the future, mirrors of the present

What images of the future are and what they say about us

What is futures thinking, really? Why does it matter? And what exactly is studied in ‘futures studies’? I answer these questions across multiple pieces.

I’ve always been amused by old ‘futuristic’ illustrations, demonstrating how people of the past imagined what life would be like today. Why are they always filled with flying objects?

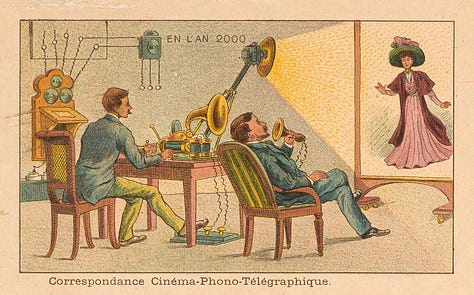

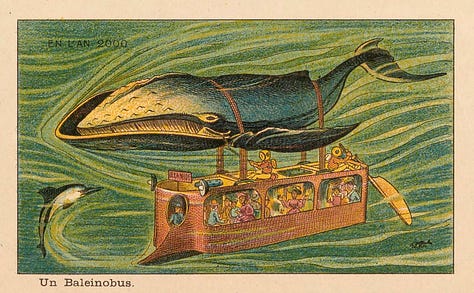

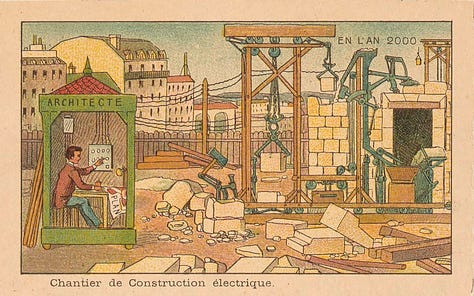

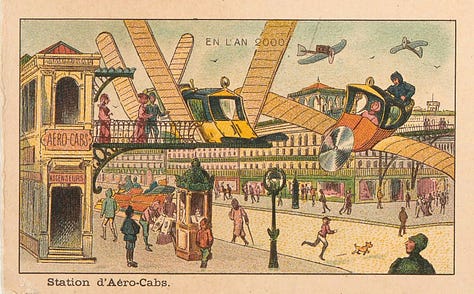

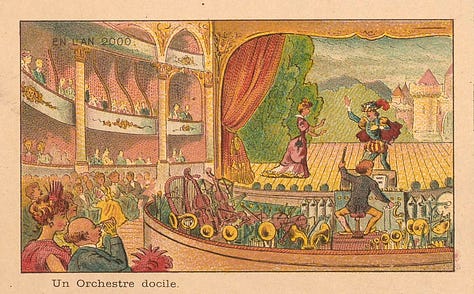

over The Forgotten Files, posted a collection of such images: French illustrations known as En L'An 2000. Created for the 1900 Paris Exposition, they envisioned life 100 years ahead, in the year 2000, the turn of a new century and millennium.1 Looking at them now, the most noteworthy thing is how little they say about our times — and how much they reveal about their own. Those images of the future are actually reflections of the time they were created, capturing the zeitgeist of 1900.

Notice the recurring themes: automation, electricity, the conquest of air and sea. It was a time of rapid transformation: electric lighting, mechanized production, new modes of transport and communication. Technology historian Thomas P. Hughes later called this era a “second creation of the world”, marked by optimism about a more functional, sophisticated, and comfortable future.

Images of the future are something we futurists study. Well, not literal illustrations like En L'An 2000 (but those too: I’ve had people draw what they imagine cities will look like in 20 years). We mean something broader: the mental imagery we all carry about what’s to come. These images are ideas of what the future might be like, shaped by our current beliefs, assumptions, extrapolations, dreams, fears, and ideologies. Just like the French postcards, they’re cultural artifacts — social mirrors, reflecting more about the present than the future. This is why it is important to unpack them.

There are no future facts

There are no past possibilities and future facts — that quote from American philosopher Robert Brumbaugh is one I particularly like. Indeed, all the possible paths of the past are already closed off, available only for alternative history fiction. All the possible paths to the future, by contrast, remain open. Even something with a 99% probability isn’t a fact until it happens.

In this sense, the future doesn’t really exist. It slips right through our hands: It hasn’t happened yet; the moment it does happen, it becomes the present — and then almost immediately, the past.

What exists are images of the future. As Australian futurist

writes in her Substack:‘The future’ is not real. It is an image, an idea, a hope, a belief, an assumption that helps us make sense of, and to act in, our worlds today. It is a concept that is knowable only when we talk about it, when we articulate our images of possible futures, and when we share them with others. We can share them in conversations, in writing, in creating something tangible, in paintings and drawings, in poetry, in any number of artifacts that we can bring into existence today. Our assumptions about our futures remain in our minds though, invisible yet powerful in shaping our decisions and actions today – until we are able to surface them into our conscious thoughts.

Remember our last week’s discussion on the different types of futures — probable, plausible, possible, and desirable — and how they’re all subjective points of view? Now we have a better term to name what they are: the different images of the future we hold today about what we think is likely, imaginable, or worth striving for. Those images are fuzzy and half-formed, like inkblots on a Rorschach test. But when we try to give those inkblots (=futures) meaning, we make them usable in the present. We give ourselves a way to navigate uncertainty.

But we don’t generate these meanings in isolation. Our education, traditions, values, consumed media and stories, our social environments, etc., all shape our images of the future. And of course, we absorb meanings from widely circulated futures narratives, those that have gained traction at a broader, cultural level.

That’s how our images of the future end up being cultural artifacts and saying so much about ourselves and our times. The whale-bus envisioned in En L'An 2000 reveals something about how that era (or, I should note, a specific group of people, including Armand Gervais, a businessman who commissioned the series, and Jean-Marc Côté, illustrator) viewed the relationship with animals and nature, how it saw the ocean as another frontier to assume. The whole series reflects a society that valued efficiency through mechanization and the conquest of new frontiers.

What about our own contemporary images? For one, World Expos still happen, and their pavilions continue to present various images of the future. Take Expo 2020: The Netherlands’ pavilion was built as a biotope showcasing technologies like mycelium-based walls and floor panels, adiabatic cooling systems, and organic-based solar panels for plants growing inside the pavilion. It embodied a changing relationship with nature and an aspiration for the fully circular economy. Spain’s pavilion, among other things, spotlighted the hyperloop model — an ultra-high-speed transportation system that promises airplane speeds at ground level with zero direct emissions. It pointed to our enduring values around speed and global connectivity, alongside sustainability.

Will mycelium replace plastic and hyperloop replace airplanes by 2125? The precise answer isn’t the point. What matters is what these images do in society today. How they shift our attitudes, steer decisions, attract investment, and focus collective attention. And that’s where politics comes in — because not all images of the future are created equal.

The politics of the images of the future

We all need images of the future to navigate uncertainty and orient our actions in the present. Whether we realize it or not, we carry some kind of mental imaginary that shapes our choices, priorities, and sense of possibility. This happens on every level of society. Individuals, communities, institutions, governments and all other different actors all rely on some image of the future to guide decisions.

Anita Rubin, one of the pioneers of futures studies, writes about how different images of the future may clash and contradict one another, just like worldviews and values do. This creates tension, which at its best is the fuel of development and change. But it can also create imbalance, conflict, division, and erosion of trust. In society, this tension shows up as politics.

Images of the future aren’t always neutral. They can be constructed, imposed, and used to steer public opinion or mobilize action. They may serve someone’s interests — or serve the common good. They can be unevenly distributed — some are amplified, others are silenced. Sometimes, they're presented as singular and inevitable — as if they’re facts. But we know that there are no future facts, and those images are no more factual than En L’An 2000’s whale-bus. Futures thinking gives us the vocabulary and lens to see those images for what they are: not facts but stories shaped by social environments, infused with subjectivity. This gives us the power to question these images and trace the values, beliefs, assumptions, dreams, fears, and ideologies they carry.

Futures thinking is anything but clever predictions about life a century from now. It is deeply connected with the present. It’s cultural commentary, political analysis, and sometimes even collective therapy for those who feel powerless in the face of change, or not represented in the dominant images of the future. Because the future is not something to predict, but something to participate in shaping.