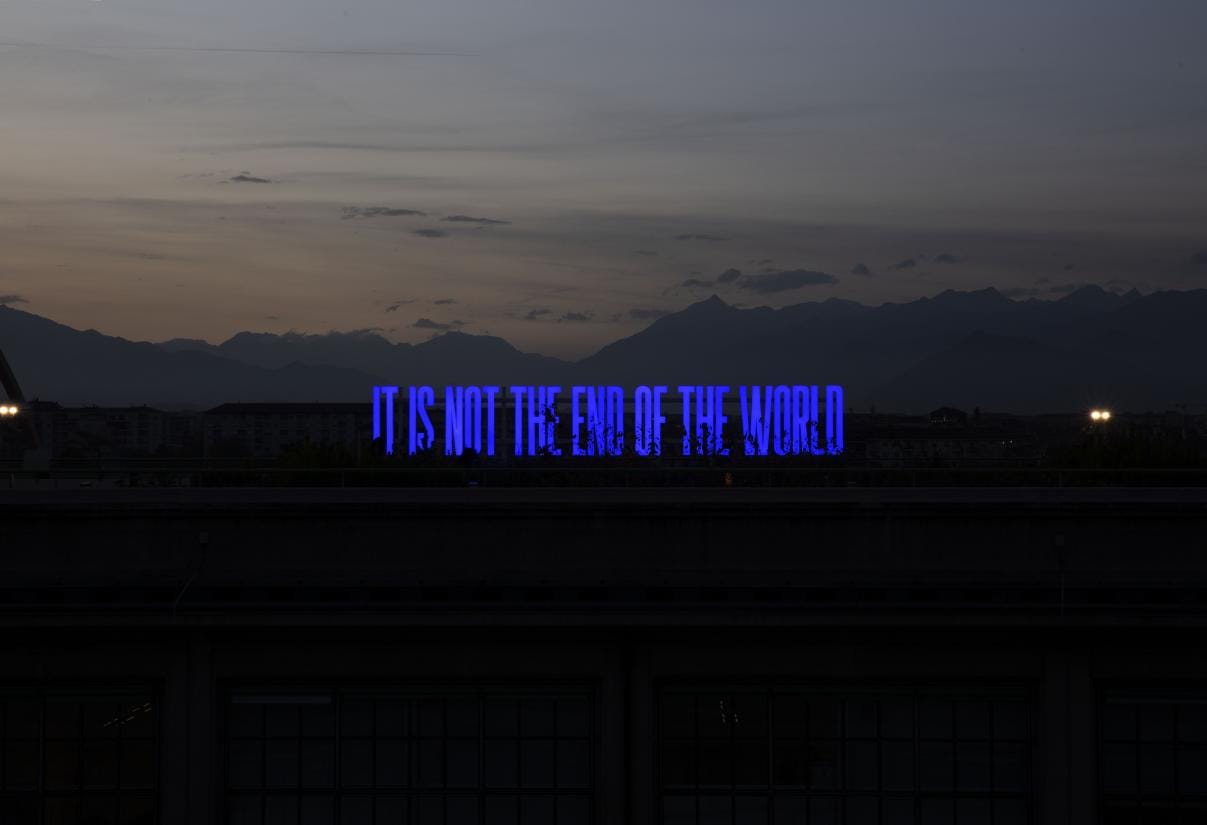

change hasn't stopped for you

the end-of-history illusion and our failure to imagine personal and societal change

When it was time for me — and most of the group I went through the master’s with — to begin our data gathering, the excitement was real. We had spent months immersed in the theory and practice of futures studies, itching to finally apply it to our own research. Many of us chose participatory methods: that’s when you bring together and guide futures thinking for people whose lives, work, or expertise sit at the center of the topic. One friend worked with schoolteachers. Another studied female entrepreneurs. I collaborated with a group of designers.

But when we met later at a seminar to share our experiences, a common feeling emerged: despite all the energy and careful planning, the envisioned futures felt... underwhelming. Not bad, just not mind-blowing. We hadn’t expected our participants to come up with mind-bending images (that’s not the task in 99% of futures research anyway). But still, we all had to face the sobering truth, that getting people to truly stretch their imagination is hard.

Futures thinking doesn’t come easy to most of us. Letting go of the present — even temporarily — is a skill we rarely train. For half of us, the future means no more than 10 years ahead — and for most, it becomes difficult to imagine beyond the 20-year mark. 53% of Americans rarely think 30 years ahead in their own lives. Futures thinking is an underused muscle: feels awkward, and quick to tire.

Lately, I’ve been exploring the cognitive biases that make futures thinking hard (or distorted). I’ve already written about the additive solution bias. Today I’d like to unpack another I keep coming back to, one I find especially foundational.

It’s called the end-of-history illusion.

When we try to envision the future, we often underestimate how much can change, even when we’re just thinking about our own lives. A 2013 study published in Science by psychologists Quoidbach, Gilbert, and Wilson confirmed this fallacy. We recognize that our lives — our values, relationships, preferences — have changed a lot in the past. And yet, we do not expect our futures to look any different from the present, as if we've arrived at a final version of ourselves. (Funnily enough, this illusion affects people irrespective of age; more than 19000 people aged 18 to 68 took part in the study.)

The end-of-history illusion is like flipping through an old photo album, marveling at all the ways we’ve changed — and then snapping a picture today and assuming this one will somehow freeze in time. It's almost funny to catch this thinking error, especially when the evidence of constant change is right in front of us.

It’s not that we’re in denial or stupid. Daniel Gilbert, one of the scientists behind the original study, suggests in his TED talk that the bias is caused by a kind of mental asymmetry between the past and the future:

Why does this happen? We're not entirely sure, but it probably has to do with the ease of remembering versus the difficulty of imagining. Most of us can remember who we were 10 years ago, but we find it hard to imagine who we're going to be, and then we mistakenly think that because it's hard to imagine, it's not likely to happen. Sorry, when people say "I can't imagine that," they're usually talking about their own lack of imagination, and not about the unlikelihood of the event that they're describing.

What stands out here is that when we struggle with picturing exactly how that change might unfold, we dismiss it as unlikely. I will come back to this point later.

I also love how

builds on this idea. He pinpoints the difference between foresight and hindsight. Hindsight, as the saying goes, is always 20/20. Tipping points of the past seem obvious, and change seems almost inevitable, once they have occurred. But, Colin writes, it is hard to foresee these moments in the future:Traveling to another country, for instance, can open your eyes to all kinds of things that you never would have perceived had you stayed put, but which are blindingly obvious in the aftermath of that experience.

If you had tried to imagine those same revelations before taking that trip, however, it’s unlikely you would have come to the same conclusions or changed your mind, your perception, in the same way. That adjustment in perspective was a necessary catalyst for your change in mindset, just as the variables you’ll encounter in the future—about which you currently know nothing, and cannot predict with any accuracy—will serve as triggers for the changes that will define who you are ten years from now.

This hindsight certainty may be exaggerated by another fallacy: explanation bias. We frame past events as more inevitable than they were, or —as economist Richard Zeckhauser puts it — underestimate the uncertainties of the past. This likely widens the cognitive gap between remembering and imagining because we remember the past as a narrative. We tell stories and assign causes. It makes the past feel orderly, and the future — chaotic.

Furthermore, some people might find peace of mind in the illusion of a stable future, especially when uncertainty brings them anxiety. There’s also a tendency to focus on and prioritize the present called presentism. It deserves separate analysis, but I’ll just flag here that it keeps us envisioning futures around the biggest current thing (looking at you, AI futures).

How the end-of-history illusion gets in the way of imagining futures

So, does this mis-prediction of change really matter, especially when we are talking not about individuals, but communities and societies? Sure, it does. Gilbert points out in his TED talk, that this thinking error “bedevils our decision-making in important ways”.

As a futurist, I see the end-of-history illusion as more than a bug of personal perception. Because of this bias, we risk not just freezing ourselves in time — but mentally freezing everything else. If we struggle to imagine change within ourselves, how can we possibly envision transformation in our community, our economy, our climate, or any of the complex systems that surround us? It is precisely due to their complexity, that we struggle with imagining any meaningful change in them. Remember what Gilbert suggested: we mistakenly think that because it's hard to imagine, it's not likely to happen.

Let’s consider three ways the end-of-history illusion impacts our capacity to imagine futures.

It tricks us into wanting more of the same

One experiment from the initial research reveals that people were willing to pay significantly more to see their current favorite band a decade into the future than to see a former favorite next week. In other words, they were biased to overpay for a future opportunity to indulge a current preference.

Let’s pause on that. We overpay — literally or cognitively — for futures that indulge our current preferences.

We tend to overvalue futures that speak to what we already like — so much so that we mistake the comfort of these imaginaries for their inevitability. This breeds a sense of complacency, being comfortable with the status quo. And who tends to be most comfortable? Most likely, those who hold privilege and benefit from how things currently are. If you're privileged in some way and you're tasked with imagining the world in 30 years, there's a good chance — consciously or not — you’ll want things to stay more or less the same.

It narrows the space for new ideas

The end-of-history illusion may also trick us into believing that we know everything there is to know about a topic. A feeling that our current knowledge is complete may lock our reasoning into a fixed frame and discourage further questioning. That’s the opposite of futures thinking — which demands unlearning, humility about the limits of our knowledge, and openness to the unknown. Such a mindset narrows our imagination and creates a false grip of what’s possible, making us more likely to dismiss signals of change and miss opportunities to challenge our assumptions.

It simplifies narratives of societal change

This quote from political scientist Michael McFaul perfectly captures the cognitive gap between hindsight and foresight, and end-of-history thinking:

(Sarah Stein Lubrano), a fellow futures-adjacent researcher, wrote a sharp, layered analysis of the end-of-history illusion connecting it to narratives about social and political change. (A thoughtful piece — don’t skip it!) She suggests that such narratives are often shaped to accommodate the end-of-history illusion. They become oversimplified and emotionally gratifying because otherwise, they cannot be imaginable (too complex!), let alone acted upon. Two common strategies emerge in political futures narratives: either working with the bias by suggesting a smooth continuation of the present, or challenging it by jolting people with extreme futures — utopias, collapses, revolutions. She writes (emphasis mine):In retrospect, all revolutions seem inevitable. Beforehand, all revolutions seem impossible.

In other words, I suspect that most political ideological systems choose their wildly simplified narratives about the past, the present, and the future precisely because we are already poorly equipped to understand the passing of time, such that we can only ever really think about ourselves as either finished products or transformable via easily-conceptualisable turns of events, like a very linear concept of progress, a nostalgic return, or a revolution. (In our personal lives, it’s more like: the self improvement glow-up, the return to the childhood home, the radical makeover). The problem, though, in both personal and political life, is that none of these easily-imaginable kinds of change are likely to be our future. It is more likely that things will simply be very, very messy, with gradual yet unimaginable change. We will not return to the past, we will not make steady progress, and no revolution is straightforward (indeed, many are disasters).

This connects deeply to how futures are framed in our collective imagination. The images that rise to the mainstream are usually quite reductive, but that’s how they stick. So when we try to imagine the future, we tend to fall back on familiar, simplified stories and the usual ways things seem to change. It is hard to make space for ambiguity, complexity, and non-linearity.

Let’s sum up. The end-of-history illusion makes futures thinking harder in three key ways:

It anchors us to the present and tempts us to project our current privileges forward.

It closes us off to new knowledge through the false belief that we already know all that matters.

It nudges us toward an oversimplified understanding of change.

Individual cognitive biases scale into collective failures of imagination, so it matters that we notice them, and try to break them.

One way to spotlight the end-of-history illusion is by reflecting on past changes. Even if hindsight is colored by explanatory bias, it is key to recognize that change has happened. In my research on the futures of cities (the one with designers), we started by listing all the ways cities had changed in the past 20 years before envisioning what might come next. It’s a simple way to warm up the futures thinking muscle.

Another way is through the futures methods themselves. Returning to Wright’s idea that it’s hard to pinpoint the moments that may shift the trajectory of change: I believe that futures tools help us conceive them. Many are designed to hold complexity without getting lost in it, to help us see potential tipping points, uncertainties, and branching paths to the future. Scenarios are a classic tool to do that.

And finally a reminder to myself: success in envisioning futures isn’t about mind-blowing ideas. It’s about growing our comfort with uncertainty, complexity, and the fact that the change hasn’t stopped for us.

Even if our brain insists otherwise.